On December 8, 1941, Hong Kong became one of the first battlegrounds in the Pacific campaign of the invading Japanese. On the same morning as the attack on Pearl Harbour, Japanese forces attacked British Hong Kong without any prior declaration of war. Japan's act of aggression was met with fierce resistance but the colony fell after 18 days of intense fighting. For three years and eight months, the people of Hong Kong lived under Japanese Occupation. This is one of a series of stories in remembrance of the Battle of Hong Kong and the dark days that followed.

PUBLISHED : Saturday, 15 August, 2015, 1:25pm

UPDATED : Saturday, 15 August, 2015, 1:25pm

My grandfather and his parents left the mainland at the age of 13 to escape the Japanese. Little did they realise the Japanese would be in hot pursuit two years later.

“The Japanese came in the morning. Their planes started to drop bombs. Boom-boom-boom…,” said my grandfather as I broached the subject with him tentatively, unsure if I really had a right to ask about their suffering.

“We had to hide in mountains near Heep Yunn School. At night, we slept in the mountains because we were scared of the bombs. We don’t sleep at home because the bombing was indiscriminate, everywhere.”

In that night of madness, all he could remember were the sounds of the bombs, the aching fear and the running.

In that night of madness, all he could remember were the sounds of the bombs, the aching fear and the running

It was December 8, 1941 that the Japanese invaded Hong Kong. My grandfather, Wong Ping-hang, was 13 years old and living near Pau Chung Street in To Kwa Wan.

He was born in Shanghai in 1929. His father worked for Chung Hwa Book Company, which was then a large publisher based in Shanghai. When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in the mainland in 1937, the company had to relocate to Hong Kong and my grandfather’s family followed suit. The journey by boat to Hong Kong took two days.

Settling in the British colony, like so many other refugees, my grandfather’s family thought they would be safe from the war raging on the mainland.

When it happened, the bombing in Hong Kong wreaked havoc and then worse days followed. My grandfather remembered how he only had groundnut oil cake mixed with porridge. I did not ask him what groundnut oil cake was but I tried to find out for myself. It is the residue of groundnut after the extraction of groundnut oil and is meant to be a fertilizer – unfit for human consumption.

“I was always hungry,” my grandfather said with barely a trace of emotion. It was a state millions found themselves in during the war. My grandmother, who was then living in the suburbs of Guangzhou then, ate only tofu residue.

People stole food regularly. My grandmother was once a victim. She was walking to the city to collect salt and kerosene. “To sustain myself for the journey, I bought a fried dumpling, which I carried on my back. But someone grabbed it away. I starved for the rest of the day.”

Both remembered the scenes of torture. They recalled a form of waterboarding torture used by the Japanese soldiers – their memory clashing so painfully with what I take for granted as a flagrant violation of basic human rights and dignity in this century.

“If you pass by the Japanese sentries on the roads and you don’t bow to them, they will call you over and beat you up. Even worse, they will pour water into your mouth till your stomach is full and step on you,” said my grandfather as he demonstrated how the Japanese waved people over – just to kick them.

But grandfather also remembered their little kindnesses.

“Some liked kids and gave you some treats, knowing we were hungry. There were good Japanese and bad Japanese.”

Some liked kids and gave you some treats, knowing we were hungry. There were good Japanese and bad Japanese

My grandmother, who met and married grandfather after she went to live in Hong Kong when the war ended, shared no such sentiments.

“It’s better not to talk about the Japanese,” she said after awhile, as she wiped her eyes. “It was a very rough time.”

It was then that I paused. I could not bear then to ask them more about that bitter past despite my curiosity. Growing up in a middle class family, I had the luxury of everything – the complete opposite of what my grandparents went through.

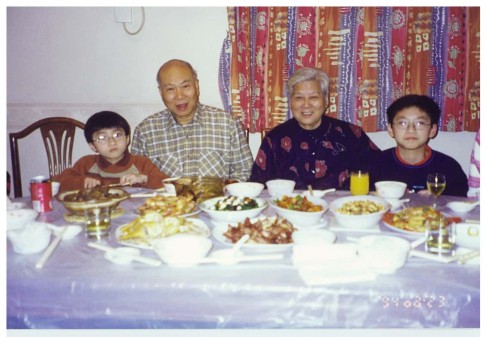

They sacrificed much to raise their four children, including my mother, their youngest child. My grandparents have shared their story and I respect them even more now than ever before.

Despite their suffering, they were the lucky ones. Hong Kong’s population shrank from 1.6 million to 600,000 after three years and eight months of occupation. Some were evicted, others died from hunger, abuse and illness.

We will never know the stories of these silent victims.

http://m.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1849579/starvation-and-stealing-life-my-hong-kong-grandparents-knew-under